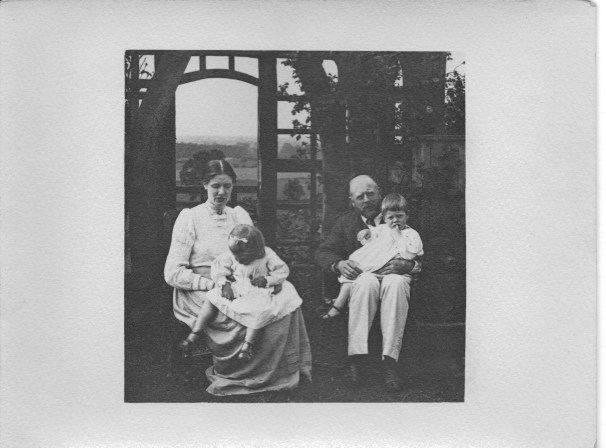

This project showcases social reform in a rural context, centred on the life of Hugh Fairfax-Cholmeley who was Squire of Brandsby from 1889 until his death in 1940.

Please see the Journal Blog

for latest research and news.

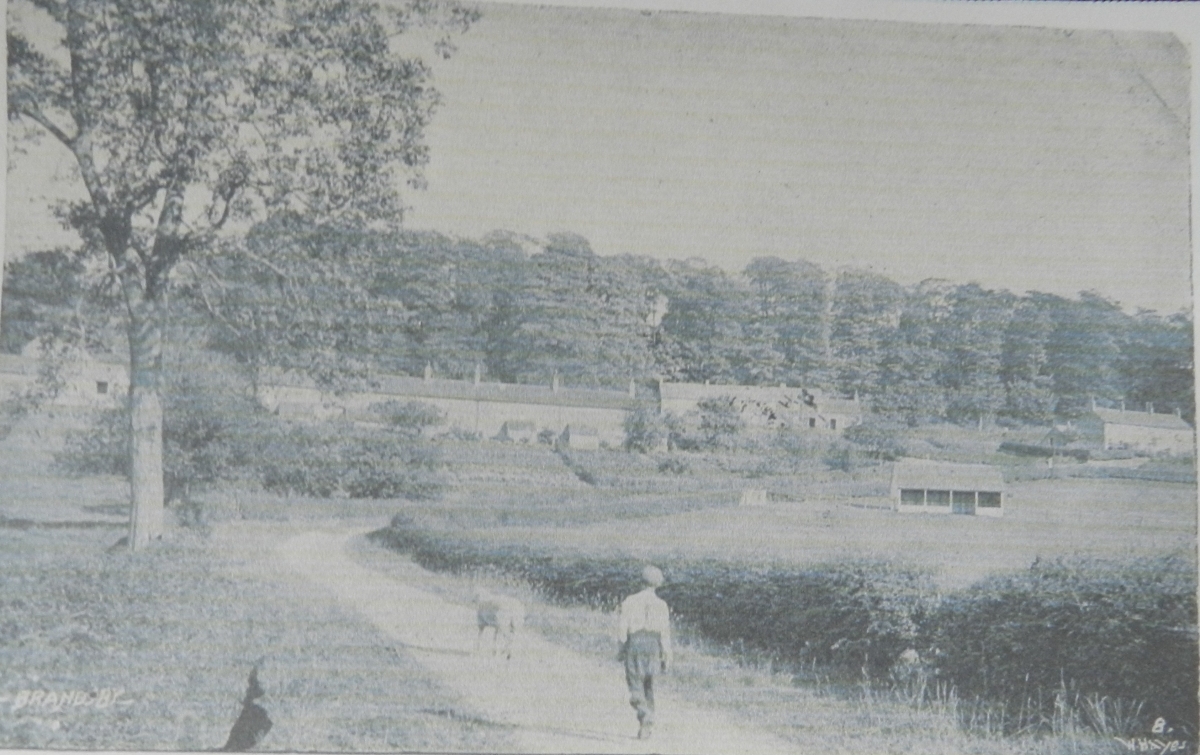

The Brandsby and Coulton estates were subject to the same problems faced by many other landowners, of declining agricultural income and increased financial obligations. At the same time rural communities were shrinking as workers left to seek better pay and conditions in towns. Hugh’s approach to managing the estate was one of embracing the need for social and scientific change and at the same time to build a healthy and well-functioning community on the estate that he loved.

Toynbee Hall: Born a Squire, Hugh set up a different style of life for himself in Brandsby and managed his estate with a view to the improvement and modernisation of every aspect of life. On leaving university, Hugh joined the recently established community of Toynbee Hall in East London in 1888. It was in East London, where he continued to maintain a presence until 1897, that Hugh formulated his ideas on social reform and made the friends and contacts which sustained his work for the rest of his life.

Social Reform: His first project was the establishment of a Reading Room in the village, through which means he planned to get people trained in committee working, he then he turned his attention to the cottages on the estate, most of which were unsanitary hovels. He promoted social events, organised evening lectures on farming methods, and by degrees brought all the farm houses and their buildings up to a satisfactory standard.

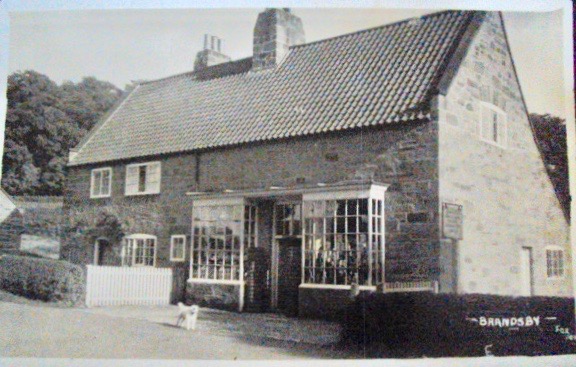

Co-operation (BATA): He was a firm believer in co-operative method and set up the Brandsby Dairy Association in 1895, which around 1900 or 1901 became the Brandsby Agricultural Trading Association (BATA). The activities of BATA were pioneers of the agricultural co-operative movement in the UK, in the sale of produce and the buying in of fertilisers and seeds. They also pioneered the establishment with the NER of a steam-motor goods service from the village to the nearest station, a scheme taken up and promoted by the Agricultural Organisation Society (AOS), of which he was a founding member.

Under Hugh’s guidance BATA continued to expand its activities, opening village shops in Brandsby and Stillington and the building and operation of a sheep dip. BATA attracted many visitors eager to learn from its co-operative schemes. This last was not least due to Hugh’s position in the AOS, as a very active member. AOS was a non-party, non-religious body, dedicated to spreading the co-operative movement in agriculture. It attracted a lot of powerful supporters and became central to the Liberal government’s policy of rural social reform. It became the operational arm of the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries. For over a decade, Hugh travelled up and down to London every month, promoting and lobbying for the interests of the land and those living on it, and for the AOS.

Communication: Hugh pioneered the establishment of a party-line telephone system at Brandsby, through direct negotiation with the Postmaster General, which scheme was also taken up by AOS and promoted widely.

Transport: Hugh’s last major structural project was the Brandsby and Haxby Light Railway, a branch line planned to connect with the NER main line York to Pickering. This project though approved and funded, was unfortunately brought to a halt by the onset of World War I.

When Hugh inherited his estate in 1889, he was already committed to social reform, through his work in the East End of London. He drew in his friends from London to advise and assist and at times many people came to visit him at Brandsby to see these exciting social experiments for themselves. His work linked to the main philantrophic and political ideas on social reform of his time and are of interest to anyone studying this period. This resource is based around Hugh Fairfax-Cholmeley’s own memoirs, and situating him within social reform as it is already documented.

Brandsby Hall and entrance to Hall Yard, original home of Hugh Fairfax-Cholmeley.

Nice to meet you!

LikeLike

Hi

I am Tom Pearson-Adams , son of Ricky. We have read your article and very much enjoyed it. Really fascinating – thank you.

Thank you

Kindest Regards

Tom

LikeLike

Hello Tom, this is a long shot, but in trying to research my “history” I came upon this website.

From 1951 to 1957 my father was gardener at Brandsby Hall and we lived in a cottage in the grounds. As a 4 to 10 year old I recall playing with the owners son Ricky who had a wonderful Austin pedal car.

Could this have been Ricky Adams?

Regards

Michael Harrington

LikeLike

Hello Michael,

As Tom left this comment on my site a few years ago, I am replying because I am not sure if he will have cause to look at it again. The Pearson-Adams did own Brandsby Hall at the time you have indicated. I visited with the Pearson-Adams 5 or 6 years ago, they were still living in Brandsby, though not in the Hall.

LikeLike

Interesting social and family history, look forward to more!

Paul Crook

LikeLike

Fascinating! Early work in agricultural cooperatives! That must have drawn Elsie to the Gung Ho movement!

LikeLike

I have been a resident of Brandsby all my life,I am also the grandson of John Ward who was stonemason who built Mill hill. Your work made fascinating reading. Thank you.

LikeLike

I have lived on and off in the area for a number of years. Brandsby is on my way to drop off groceries to a ‘Covid-19 isolated’ father. It occurred to me to find out a little more about Brandsby and I have very much enjoyed reading these articles – how interesting. Thank you.

LikeLike

Thanks Jennie, so pleased you enjoyed the website!

LikeLike